[ Plant

part | Family | Aroma

| Constituents | Origin

| Discussion |

- Synonyms

| pharm |

Fructus Capsici |

| Danish

|

Paprika |

| Dutch |

Paprika |

| English

|

Bell pepper, Pod pepper,

Sweet pepper |

| Esperanto

|

Papriko |

| Estonian

|

Harilik paprika |

| Finnish

|

Ruokapaprika, Paprika |

| French

|

Piment annuel, Piment doux,

Paprica de Hongrie, Piment doux d'Espagne |

| German

|

Paprika |

| Greek |

Pipería |

| Hindi |

Deghi mirch |

| Hungarian

|

Paprika, Édes paprika,

Piros paprika, Fűszerpaprika |

| Icelandic

|

Paprikuduft |

| Italian

|

Peperone, Paprica |

| Papiamento

|

Promenton, Promčntňn |

| Portuguese

|

Pimentăo doce |

| Polish

|

Papryka roczna |

| Romanian

|

Ardei |

| Spanish

|

Paprika, Pimiento dulce,

Pimiento morrón, Pimentón |

| Swahili

|

Pilipili hoho |

| Swedish

|

Paprika |

| Tibetan

|

Sipen ngonpo, Si pan sngon

po |

- Mexican chile cultivars

- A large number of names for different cultivars is used

in Latin America, especially México. Fresh and dried

chiles are often referred to by different names. The

following table lists some of the most common types.

| Name fresh |

Name dried |

Pungency |

| Anaheim

(California) |

chile pasado |

low |

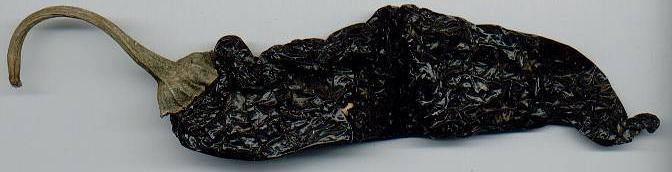

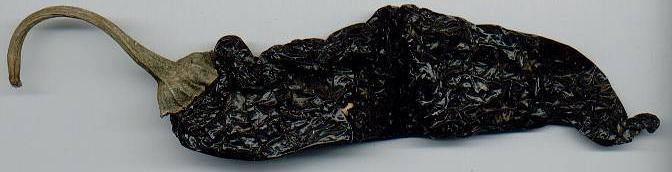

| Chilaca |

pasilla (chile

negro) |

low |

| Jalapeńo |

mora (morito)

chipotle (chile ahumudo, chile meco) |

medium |

| New Mexico |

chile pasado |

low |

| Poblano |

mulato ancho |

low |

| Serrano |

|

high |

|

| A European breed of paprika |

- Used plant part

- Berry fruits. Removal of seeds and veins results in a

less pungent and more brightly coloured product.

- Plant family

- Solanaceae (nightshade family).

- Sensoric quality

- Sweet and aromatic. Some qualities show no pungency at

all, others are fairly hot.

- Main constituents

- The pungent principle, capsaicin, is contained only in

small amounts, as low as 0.001 to 0.005% in

"mild" and 0.1% in "hot" cultivars.

(see chiles for details on capsaicin). Apart from

capsaicin, the taste of paprika is mostly due to

essential oil (<1%; with long-chain aliphatic

hydrocarbons, fatty acids and their methyl esters);

paprika scent is mostly do to a range of

alkylmethoxypyrazines (e.g., 3-isobutyl 2-methoxy

pyrazine, "earthy" flavour). Ripe paprika

contain up to 6% sugar.

Furthermore, paprika contains

sizable amounts (0.1%) of vitamin C; this substance was

first isolated from ripe paprika pods by the Hungarian

chemist Albert Szent-György, who later won the Nobel

Prize for this work.

|

| Black Prince, an ornamental

breed rich in anthocyanin pigments (tepín-

or piquín type). |

Paprikas derive their colour from red

(capsanthrine, capsorubin and more) and yellow

(cucubitene) carotenoids ; their total amount in dried

paprika is 0.1 to 0.5%. Cultivars lacking the red

pigments appear yellow or orange when ripe. Some

varieties of paprika contain pigments of anthocyanin type

and develop dark purple, aubergine-coloured or almost

black pods; in the last stage of ripening, however, the

anthocyanins get decomposed, and the unusual darkness

thus gives way to normal orange or red colours.

- Origin

- Since different varieties of bell peppers have been

cultivated in America long before the arrival of the

Europeans, their native countries cannot be unambiguously

determined; South American origin is, however,

established for all species of genus Capsicum,

which emerged probably in the area bordering Southern

Brazil and Bolivia. Thence, the species moved to the

North, being dispersed by birds.

|

| Prairiefire, an ornamental of

piquin type. |

The three species C. annuum, C. frutescens

and C. chinense evolved from a common ancestor

which was located in the North of the Amazonas basin

(NW-Brazil, Columbia). Further evolution brought C.

annuum and C. frutescens to Central America,

where they were finally domesticated (in México and

Panamá, respectively), whereas C. chinense moved

to the West and was first

put to cultivation in Peru; (although

today it is not much cultivated in South America). Two

other species were first cultivated in Western South

America: C. baccatum in the Peruvian lowlands and C.

pubescens at higher elevations, in the Andes (Peru,

Bolivia, Ecuador). See chile for more information about

these species.

As paprika plants tolerate nearly every climate, the

fruits are produced all over the world. A fairly warm

climate is, however, necessary for a strong aroma;

therefore, in Europe, Hungarian paprika has best

reputation; the best comes from the Kalocsa region. In

the Unites States, California and Texas are the main

producers.

- Etymology

- In many European languages, the name of this spice is

somehow derived from the name of pepper, owing to the

many confusions of pepper with other spices (for another

example, see allspice).

So, in English it is called bell

(or pod) pepper (because of shape) or sweet

pepper (because of taste; cf. French piment doux

or Spanish pimiento dulce); most confusingly, the

English plural peppers always seem to imply

paprika and never pepper!

|

| Flower of C. annuum |

For reasons of clarity, the term pepper for Capsicum

species will be totally avoided here. Instead, I will use

paprika, which is moderately common in English

(for the dried spice), more so in other tongues; it was

loaned from Serbian pŕprika or Hungarian paprika

(both Serbian and Hungarian cuisine make much use of

middle-hot Capsicum powder). Ultimately, also paprika

derives from the name of pepper (Serbian pŕpapr).

The botanical species name Capsicum is a

neo-Latin derivation of Greek kápsa "box,

capsule" and the refers to the shape of the fruits.

There is an alternative, though much less probable,

derivation starting from a related verb, káptein,

translated "bite". The verb's basic meaning,

however, is "seize, grasp"; it may also mean

"grab using the teeth; bite", but even from

this meaning it's a wide sematic shift to

"biting" in the sense of "pungent".

The old German name Beißbeere "biting

berry" for hot chiles is probably a loan

translation.

The genus name annuum means "annual"

(Latin annus "year"). This name was

chosen most unfortunately, because in the absence of

winter frosts, paprika and its relatives can survive

several seasons. In its natural habitat, paprika grows

into large perennial shrubs.

|

| Chinese five-coloured paprika cultivar.

|

The bright red colour of ground paprika is

a remaining impression for everyone who has had an opportunity to

visit a market in the Near or Middle East (from Morocco via

Turkey to Northern India). In these regions, the spice is equally

valued for taste as for colour. Its subtle, sweet flavour is

compatible with hot and spicy dishes, but also mild stews profit

greatly from it. Since paprika contains significant amounts of

sugar, it must not be overheated, otherwise the sugar turns

bitter. Frying paprika powder in hot oil is therefore critical

and must last no longer than a few seconds.

A spice mixture from Central Asia employing paprika is baharat,

a fiery composition from the countries around the Gulf of Persia.

As many other mixtures from Arabic-influenced cuisines (see

grains of paradise on Tunisian gâlat dagga, cubeb pepper

on Moroccan ras el hanout and long pepper on Ethiopian berebere),

baharat contains both pungent and aromatic spices: black

pepper, chiles and paprika provide a pungent background and

nutmeg, cloves, cinnamon and cardamom contribute aromatic

flavour; the mixture furthermore contains cumin and coriander

fruits, all of which are ground to a fine powder. Baharat

is mainly used for mutton dishes; most commonly, the mixture is

shortly fried in oil or clarified butter to intensify the

fragrance.

In Europe, especially Hungary and the Balkan countries are

known for much paprika consumption, less so the Mediterranean

countries, although some Spanish cultivars are famed (e.g., romesco).

Even in those countries where hot chiles are disliked, mild

paprika types are valued as spice and especially popular for

stewed or barbecued meat and sausages. Paprika appears very

frequently in commercial spice mixtures.

|

| Hungarian cherry paprika (cseresznyepaprika)

|

It is not fully clear how the paprika arrived in Hungary, but

there is no doubt that the fruits were brought by the Turks in

the 17.th century, who might have encountered them before in

Portuguese settlements in Central Asia. Anyway, paprika became

quickly naturalized and have since proved an important flavour in

Hungarian cuisine. Still, some of the best paprika cultivars in

Europe are found in Hungary. An example is the cherry paprika

("cherry pepper", cseresznyepaprika), which has

medium pungency (well, enough for most Europeans) but an

excellent flavour. This is one of the few non-American paprika

cultivars that can rival with Mesoamerican, particularily

Mexican, varieties. Cherry paprika can be dried and ground to a

rather piquant paprika powder, but in Hungary it is also eaten

fresh and served as a kind of table condiment. Lastly, it is very

good pickled.

In Hungarian cuisine, different grades of paprika of varying

pungency are used. There are four basic grades: különleges

(special paprika), csemege (delicatesse paprika), édesnemes

(sweet and noble paprika) und rózsa (rose paprika). Other

than in México, these grades do not stemm from distinct paprika

cultivars; the differences entirely come from the degree of

ripeness at harvest time and selection of pods by size; a chief

point accounting for the differences in pungency, colour and

flavour is the proportion of mesocarp (fruit wall), placenta and

seeds which are ground together. Különleges consists

only of selected mesocarps of fully ripe harvested, flawless

paprika fruits; it has a mild, delicate flavour, no pungency and

a bright red colour. In the more common grade csemege, the

paprika flavour is stronger, but it is still almost non-pungent. Édes-nemes

has a subtle pungency, and rózsa is a piquant product

with still good paprika flavour, but markedly reduced colour; for

its production, the fruits may be plucked in a partially riped

state and be subject to an artificial ripening process. Rózsa

is the grade most often available in other countries.

To produce the milder grades, one needs much mesocarp, but

only little veins, placenta and seeds. The excess material is

then ground to yield a hot paprika powder (cípôs) of

orange-brown colour and poor flavour; it is almost as pungent as

common chile powders, e.g., cayenne pepper. In some literature,

additional grades between rózsa and cípôs are

mentioned (gulyás, erôs).

The Hungarian "national dish" is gulyás,

which basically means "cattleman", and is also used to

name the cattleman's favourite food: a thick and spicy soup made

from beef, varying vegetables (potatoes, carrots) and a

particular type of pasta. To get the right flavour and colour,

chopped onions are lightly fried in pig's lard; when the onions

take a pale yellow colour, paprika powder is stirred in and fried

for a few more seconds before the remaining ingredients are

added. It is the art of goulash making to fry the paprika powder

as long as possible (to bring out its flavour), but stop the

frying before it turns bitter (which may happen very quickly).

This food has been much copied but also bastardized in the

cooking of other European countries; the

"internationalized" versions (goulash) are often stews,

not soups, made of beef or pork in a thick sauce made from onions

and paprika powder. In Austria, often caraway is used for the

seasoning. In Hungary, such a dish would be not be called a gulyás

but a pörkölt; a pörkölt with sour cream added

is a paprikás. Another well-known Hungarian food is lecsó,

a tasty stew from nonpungent capsicum vegetable, tomatoes, onions

and sometimes smoked bacon. Lecsó is flavoured with hot

paprika.

Nunpungent paprika grown as a vegetable (often called bell

pepper in English, although they aren't peppery at all) are an

Eastern European invention, probably from Bulgaria. They arose

quite lately, at the end of the 19.th century, and have become a

popular food all over the world since then.

Although chile and paprika do not stem from Central America,

the art of their cultivation has reached its highest peak in

México. In México, the species Capsicum annuum is grown

almost exclusively; it is unique among all Capsicum

species because there are both pungent and mild cultivars. See

chile for a discussion of the other species.

|

| Chile tepín, flower and ripe

fruit |

It is often speculated that the variety called tepín

or chiltepín (chilctepín, "flea chile",

C. annuum var. aviculare or C. annuum var. glabrisculum),

which grows wild in the North Mexican desert (Sonora) and also in

parts of the US (Texas), might have been put to cultivation by an

ancient Mexican people and has, thus, become the actual ancestor

of all cultivated C. annuum varieties. By this line of

reasoning, the chiltepín would be the ancestor of most of

today's chile and paprika cultivars grown on all continents with

the sole exception of Southern America, where still today

botanically different species dominate (see chile for details).

It is, however, difficult to explain (i) how the chiltepín

could have travelled from its diversification locus (Amazonas

basin) that far into the North without human help, and (ii) why

all early records of chile cultivation point to Central and

Southern México, never to the North. So the chiltepín is

more probably a cultivar that has escaped back into the wild, not

an original wild form.

The chiltepín is quite hot and can be fiercingly hot;

it is much used for North Mexican cuisine and has quite recently

established itself on the US market, fuelled by the large number

of Mexican immigrants and the general interest in Mexican and

other spicy food. It should be noticed that the tepín is still a

wild plant, and all of the crop is collected from the wild. So

far, all cultivation attempts have failed.

In México, there exists a continous spectrum of paprika pods,

from the very mild to the very hot. Confusingly, all of them are

usually referred to as chiles, and indeed they are all one

botanical species. To keep things more compatible with other

countries (where there is just hot chile and mild paprika, but

nothing in between), I will not use the term chile for mild

varieties, but stick to the name paprika for all mild to

medium hot Mexican chiles.

|

Chiltepín

pods

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dried chile

piquin

|

|

Mexican chiles and paprika are known and identified by their

local names. The smallest of these are just one or two centimeter

long: Besides the above-mentioned tepín, there is a whole

class of cultivars called pequín or piquin with

small, elongated and quite hot fruits. On the other side of the

spectrum, there are large-fruited varieties with pods larger than

15 centimeters: Anaheim, chilaca, poblano,

and New Mexico. Mexican cooks often use several varieties

of fresh and/or dried chiles/paprikas for one recipe, because

their chief goal in chile usage is not so much heat but flavour,

which varies strongly between the different varieties.

Some of the Mexican capsicum cultivars are rather large,

thick-fleshed and show only low heat. One of the most popular

varieties is the poblano, whose large size (up to 12 cm

long and 7 cm broad) and moderate heat make it even possible to

use it as a vegetable: The famous recipe chiles rellenos

consists of red or green poblanos stuffed with cheese,

which are dipped in batter, deep-fried and served with a tomato

sauce. Poblanos and other thick-fleshed varieties cannot

simply be dried, but must be roasted and peeled or smoked before

usage. According to the exact drying procedure, the same capsicum

cultivar may be sold under different names; e.g., a dried poblano

may be an ancho or a mulato. Dried capsicum mostly

stems from ripe fruits, whereas fresh ripe capsicum is often hard

to obtain because of short shelf life.

|

| Poblanos are

large-fruited paprikas with a fruity flavour and

a mild, pleasant pungency. |

|

|

|

|

| The ancho is a dried

poblano; it plays an eminent rôle in the

cuisines of México. |

|

| |

|

|

|

The chile

pasilla (also called chile negro) is

one of the most common Mexican chiles

|

| |

|

|

| The Mexican costeńo amarillo

chile, dried |

Its fresh form, called chilaca,

is dark green, almost black; it is used much more rarely.

|

Much of the secrets of Mexican cookery lies in the properties

of dried capsicum. Roasting enhances the natural aroma of

paprika, smoking may add new accents and given the multitude of

different cultivars, a Mexican cook has almost unlimited

possibilities to make his choice from. Salsas (see long

coriander) may be made from either fresh or dried capsicum, or

both. For sauces whose preparation involves long simmering

periods, dried capsicums are unanimously preferred. Often, the

dried capsicums are roasted again and rehydrated in hot (but not

boiling) water before usage. This procedure again intensifies the

flavour.

Mild varieties (like ancho, mulato and pasilla,

which are often referred to as "the holy trinity") are

commonly combined with less aromatic, but more pungent cultivars

like the de arbol or the smoky chipotle. The

results are often phantastic.

|

The Mexican pasilla de Oaxaca

chile, dried and smoked

|

| |

|

Dried chile

pulla from México, Perú

|

|

|

The Mexican chipotle chile

is a dried and smoked ripe jalapeńo.

|

|

As ripe chiles cannot easily be stored, the Mexican Indians

have invented a smoking precedure that yields chiles of unique

culinary value. The most common smoked chile, the chipotle,

has become an indispensible ingredient in the cooking style of

the southwestern US (Texas, New Mexico, Arizona), as it provides

a delicious balance of heat and smoky flavour. To use chipotles,

they are normally ground or finely shredded befor usage; an

exception to this rule are chipotles en adobo, which are

whole chipotles stewed in a seasoned tomato sauce. In this

form, the chipotles are used either as a snack or garnish

for those who can stand it, or more commonly as an ingredient to

flavour other foods.

Mexican mole sauces are very complex mixtures of

several different capsicum cultivars plus a large variety of

other ingredients; preparation takes quite a time, in some cases

even days. Most mole call for dried chiles. Oaxaca, a

province in Central México, is regarded the home of these

sauces: In Oaxaca, seven classical recipes (los siete moles)

are traded from generation to generation.

Most moles contain different kinds of nuts and seeds,

which add body, furthermore spices like cinnamon and allspice,

and aromatic vegetables (tomatoes, tomatillos). Corn flour (masa

harina) or dried tortillas are used to thicken. It is

essential to select the proper chiles: For example, mole negro

("black mole") needs the costly and rare chilhuacles

negros, but mole amarillo ("yellow mole") is

prepared with fresh guëros, a more pungent and less

aromatic variety. The most famous recipe is mole rojo

("red mole", also known as mole Poblano); see

sesame for details. For green mole (mole verde), see

Mexican pepper-leaf.